First time seizure

Seizures can be generalized or focal, with various subtypes. Initial evaluation includes history, lab tests, and neuroimaging, primarily for loss of consciousness. Not all seizures need medication; it depends on recurrence risk and causes. Hospitalization may be necessary in certain cases. Decisions on starting medication after a first seizure depend on factors like abnormal neurological findings and EEG results. Patients should be aware of triggers and activities to avoid, especially regarding driving. Common antiseizure drugs include levetiracetam, phenytoin, and valproic acid, with regular monitoring for side effects and drug levels.

Overview of Seizures: Types and Characteristics

Seizures are a common neurological issue classified as generalized or focal based on the onset of electrical activity in the brain. Focal seizures with retained awareness (previously simple partial seizures) manifest based on their origin site, e.g., flashing lights for seizures originating in the occipital cortex. Focal seizures without awareness (previously complex partial seizures) are more common, often involving clouded consciousness and automatisms like chewing or lip smacking. Generalized tonic-clonic seizures (grand mal seizures) involve a sudden loss of consciousness, stiffening of muscles, followed by jerking movements and often a bitten tongue. Absence seizures, mainly in children, are characterized by brief episodes of staring and lip smacking. Myoclonic seizures involve sudden arm muscle contractions, occurring singly or in clusters. (1, 2, 3)

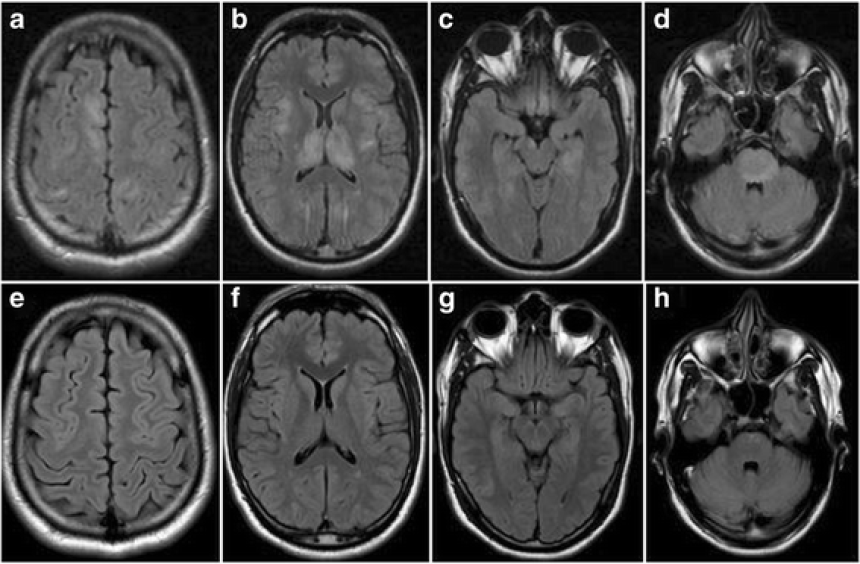

Initial Assessment and Evaluation of Seizures

The goal in assessing a first seizure is to determine if it's caused by a treatable brain condition. This includes characterizing the event, ruling out alternative diagnoses, and conducting laboratory tests (blood glucose, CBC, CRP, calcium, magnesium, renal and liver function tests, urinalysis, toxicology screens) and an ECG. Brain MRI is crucial for evaluating structural abnormalities. (4)

Management and Treatment Strategies

Non-Pharmacological Approach

Most seizures do not require antiseizure drug therapy. For hypoglycemia-induced seizures, intravenous dextrose is used. Hospitalization is necessary for severe cases, like those with incomplete recovery, prolonged postictal states, or status epilepticus. Factors increasing seizure recurrence risk include seizure duration, type, and EEG abnormalities. (5, 6)

Pharmacological Treatment

The decision to initiate antiseizure drug therapy considers multiple factors, including patient's neurological and overall health status. In critical cases, intravenous drugs are used for rapid effect. For first unprovoked seizures, factors like neurological examination, EEG abnormalities, and MRI findings guide treatment decisions. (7)

Patient Education and Lifestyle Considerations

Patients should be informed about seizure triggers (sleep deprivation, alcohol, certain medications) and avoid high-risk activities. Driving restrictions vary by location and seizure-free duration. (8)

Common Antiseizure Medications and Monitoring

Common antiseizure drugs include levetiracetam, phenytoin, and valproic acid, with specific dosing and adjustment guidelines. Regular monitoring is necessary for blood counts, liver and renal function, drug levels, and side effects like CNS depression, skin reactions, and psychiatric symptoms. Patients should consult their physician before starting new medications. (9, 10)

References

1- Hauser WA, Rich SS, Annegers JF, Anderson VE. Seizure recurrence after a 1st unprovoked seizure: an extended follow-up. Neurology 1990;40: 1163-70.

2- Camfield PR, Camfield CS, Dooley JM, Tibbles J, Fung T, Garner B. Epilepsy after a first unprovoked seizure in childhood. Neurology 1985;35: 1657-60.

3- Hauser WA, Rich SS, Lee JR, Annegers JF, Anderson VE. Risk of recurrent seizures after two unprovoked seizures. N Engl J Med 1998;338: 429-34.

4- Bergey GK : Management of a first seizure. Continuum (Minneap Minn)

2016; 22: 38-50.

5- Marson A, Jacoby A, Johnson A, Kim L, Gamble C, Chadwick D, et al. Immediate versus deferred antiepileptic drug treatment for early epilepsy and single seizures: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2005;365: 2007-13.

6-Breen DP, Dunn MJ, Davenport RJ, Gray AJ. Epidemiology, clinical characteristics, and management of adults referred to a teaching hospital first seizure clinic. Postgrad Med J 2005; 81:715.

7- Seneviratne U: Management of the first seizure: An evidence based

approach. Postgrad Med J 2009; 85: 667-673.

8-Krauss GL, Ampaw L, Krumholz A. Individual state driving restrictions for people with epilepsy in the US. Neurology 2001; 57:1780.

9-NA:Diagnosis and management of epilepsy in adults. Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, Healthcare Improvement Scotland. Edinburgh, 2015.

10-Glauser T, Ben-Manachem B, Bourgeois B, Cnaan A, Guerreiro C, et al. Update ILAE evidence review of antiepileptic drug efficacy and effectiveness as initial monotherapy for epileptic seizures and syndromes. Epilepsia 2013; 54: 551-563.